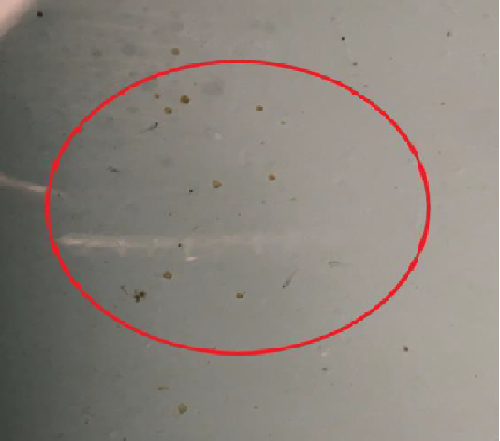

Fat Mucket juveniles produced during the 2019 pond season in Pond 14 North.

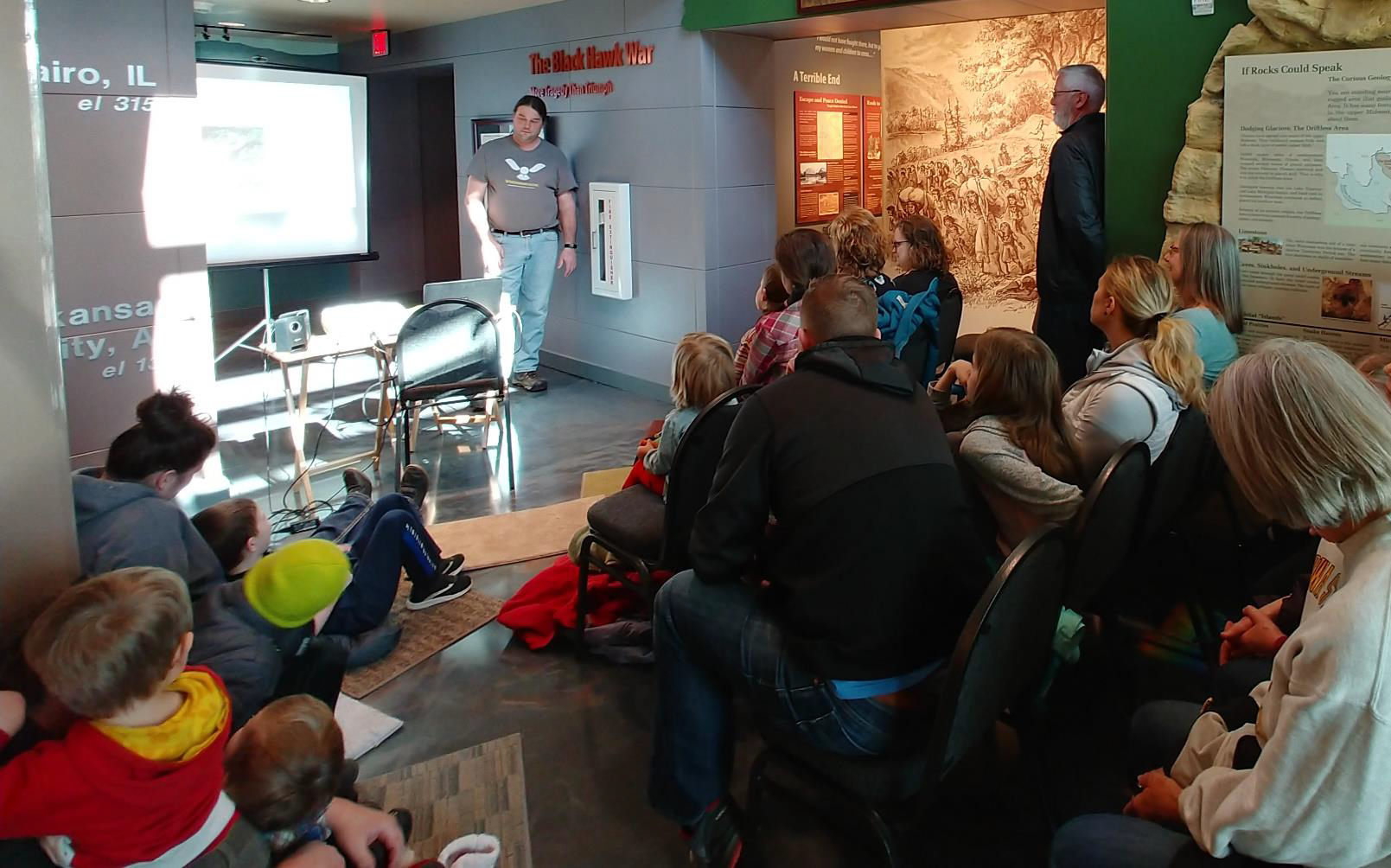

Mussel culture has grown throughout the last several years, but it is nowhere near the same place fish culture is. When it comes to fish, we have over a century of science to fall back on. When we run into a problem, there is a very good chance someone has had that same problem and tried different solutions. Freshwater mussel culture, on the other hand, does not always have that knowledge to fall back on. That means we get to be the tinkerers.

In 2019, we completed a study looking at mussel survival and growth in the twin ponds at the east edge of the property, ponds 14 north and south. We looked at water quality and food quantity in an organically fertilized pond vs an inorganically fertilized pond. While we didn’t see any difference in survival, we were able to grow substantially larger mussels in the inorganic pond, with no effect on fish production in either pond.

This year, we are trying something similar with additional mussel species. The inorganic vs organic pond is still in play, but we went without Aquashade in the inorganic pond and reserve the right to add algaecide if necessary. Aquashade dyes the water to limit sunlight penetration, slowing primary production and growth of aquatic vegetation. Algaecides can be toxic to mussels, but we want to see whether the small amounts used in typical fish production are problematic. Every little piece of information we can glean from these small-scale studies can be used to increase our ability to grow more and bigger mussels to help us achieve our mission.

By Nick Bloomfield