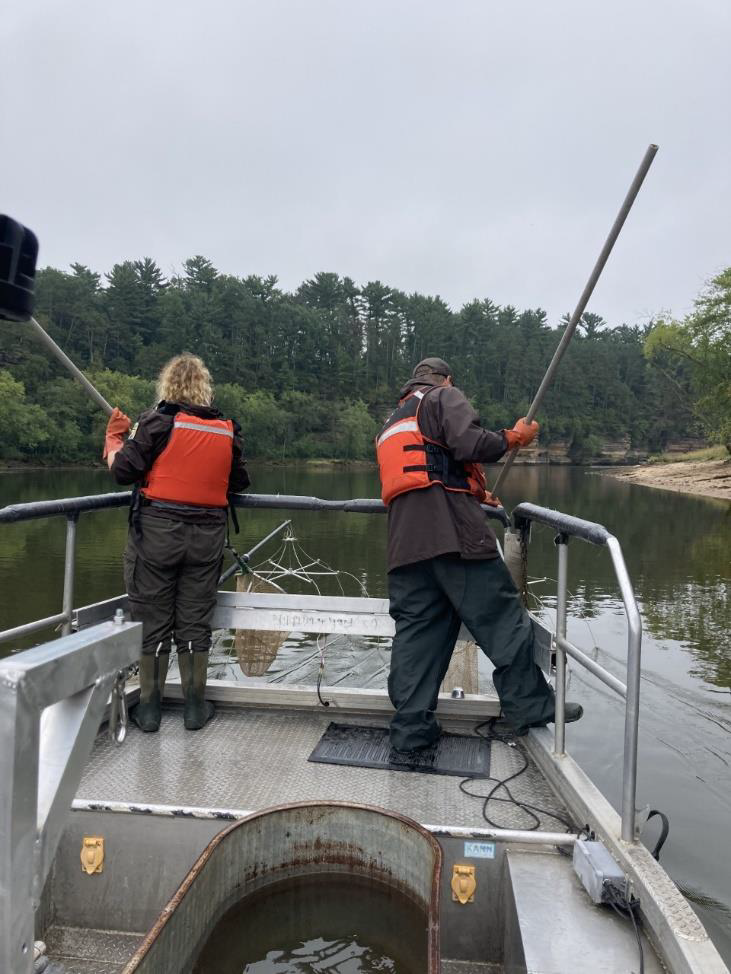

Our mussel biologists spent a few chilly days in autumnal Michigan collecting broodstock recently. Collaborating with the Michigan ES office and biologists from the USGS Columbia Environmental Research Center (CERC) meant that more people could cover ground in these Lake Erie tributaries to collect enough brooding females to execute not one, but three projects. Unlike the large mussel beds in many large rivers, mussels are distributed in random pockets in these small streams. This means that a crew looking for mussels might crawl and feel the stream bottom for a quarter of a mile to find the 15 brooding mussels needed for a project. This sometimes makes for rather a cold adventure.

USFWS worker collecting mussels in a river. Photo: USFWS.

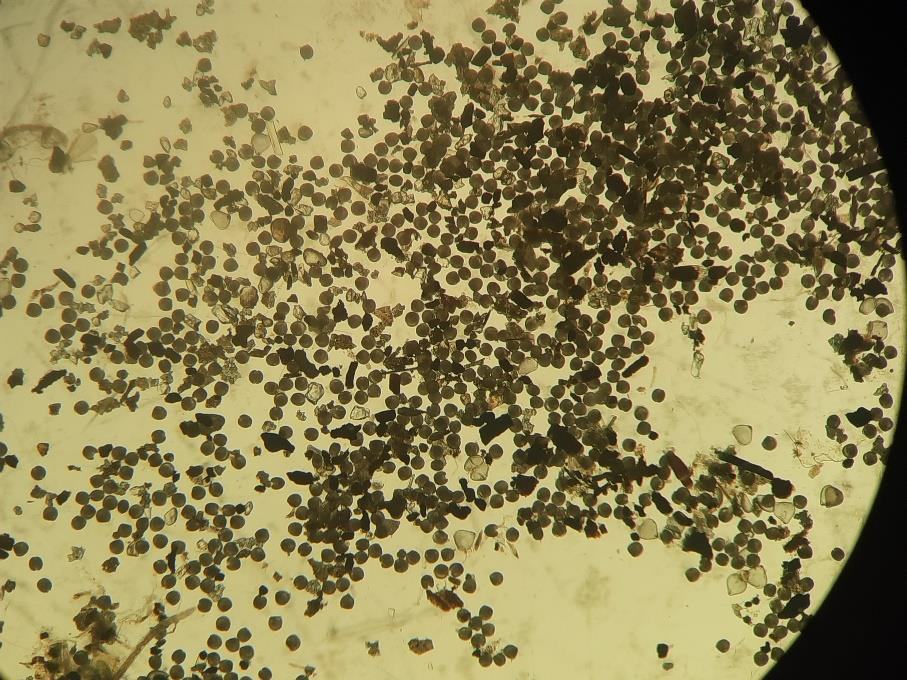

Two of those three projects are concerned with the potential impact of contaminants on mussels. These projects will be completed in the lab at CERC, one of the leading labs doing freshwater mussel toxicology research. The third project focuses on returning mussels to Michigan streams and then trying to observe measurable positive changes in water quality and biological activity. The contaminants being assessed are PFAS, per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances, a group of contaminants of emerging concern because of their wide use and unknown impacts to aquatic organisms and because of its long life in the environment (sometimes referred to as a forever chemical), and mercury, a much more widely-recognized contaminant, with known impacts to human health from the 1800’s. What is unknown is its impact on freshwater mussels.

The third project is being designed to hopefully quantify the ecosystem uplift created by the reintroduction or augmentation of mussel populations. Historically many of the great lakes streams had many more mussels, but in some areas anthropogenic declines as a result of industrial pollution and urbanization etc. are beginning to plateau. The plan is to begin to return mussel densities and diversities to historical levels and then to potentially look at changes in nutrient levels, insect and fish communities, or even simple water quality values to see if there are observable changes. This type of project is challenging because the variable environment can result in no observed change, not because the mussels aren’t positively changing the water quality, or repackaging nutrients, but because of increases in nutrients, new sources of pollution or even a year of above average precipitation.

As always, opportunities to work together in the field make for the most-memorable days, and the unexpectedly beautiful suburban streams, colored by fall foliage certainly contributed. We’re looking forward to more days in the field and to rearing the juvenile mussels from the females collected for the toxicology and reintroduction/augmentation projects.

By: Megan Bradley

We had a very successful year with the two beehives located at the Genoa National Fish Hatchery. The hives produced approximately 10 gallons of honey. A special thank you to the 3rd grade students from Southern Bluffs Elementary School who came out to help with the harvest. Students learned about the importance of pollinators like honeybees. According to the Natural Resources Defense Council, bees pollinate an estimated 1/3 of our food crops and up to 90% of wild plants. The students also helped uncap the honey and got the opportunity to hand crank an extractor to release the honey from its frames. To end the experience, the students were able to enjoy the honey they had just spun!

We had a very successful year with the two beehives located at the Genoa National Fish Hatchery. The hives produced approximately 10 gallons of honey. A special thank you to the 3rd grade students from Southern Bluffs Elementary School who came out to help with the harvest. Students learned about the importance of pollinators like honeybees. According to the Natural Resources Defense Council, bees pollinate an estimated 1/3 of our food crops and up to 90% of wild plants. The students also helped uncap the honey and got the opportunity to hand crank an extractor to release the honey from its frames. To end the experience, the students were able to enjoy the honey they had just spun!